THUNDER BAY – The decision to remove Dr. Seuss books flagged as racist by the author’s estate wasn’t made lightly, the Thunder Bay Public Library says.

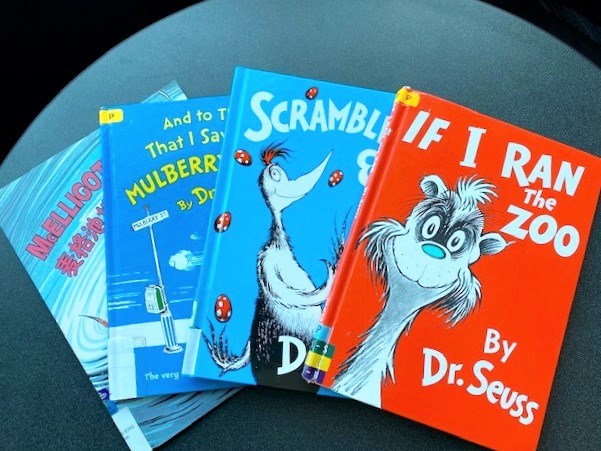

The issue became an ideological live wire after Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced in March it would cease publication of six of his early works.

The announcement came after a review by experts including educators that found the books contained harmful portrayals of non-white characters, the estate said.

The Thunder Bay Public Library pulled the titles from shelves the following day, pending a review. Two days later, the library announced the removal would be permanent.

It also committed to a broader review of its collections policy in light of the episode, promising consultation with racialized groups.

The incident clarified the need to engage the community on the diversity – and limits – of its collection, senior TBPL staff said in a March interview.

The removal was a “collective decision” that came after a review against its collections policies and thorough discussion among library management, its board of directors, and a librarian group, said CEO and chief librarian John Pateman.

There was no doubt the concerns had to be taken seriously, he said.

“What struck us straight away was the request for these books to be withdrawn came from the foundation that manages the Dr. Seuss estate," he said. "It wasn’t coming from a political direction, it was literally the source of the works themselves.”

Library as anti-racist institution

The library’s decision was grounded in its commitment to operate as an anti-racist institution, Pateman said.

Staff initiated a review of the six books after Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced it would stop publishing them. The books were reviewed against TBPL collections management policies, but the decision to remove a book always depends on context, Pateman stressed.

A book can be removed from the collection if it’s “considered to be inconsistent with TBPL values, vision, purpose and strategic direction,” among other criteria, according to library policies.

The organization’s five strategic directions include “challenge institutional and systemic racism” and “cultivate diversity and inclusion.”

There’s a strong argument for preserving some objectionable works, said director of collections Angela Meady – but the public library may not be the place to do it, at least when it comes to children’s material.

“If we were an academic library, we’d be having a completely different discussion. I’d say, 100 per cent we’ll keep these books – they’re part of Seuss’s legacy, they tell the story,” she said.

“But as a public library where children are browsing the shelves, making their own decisions, [when] we don’t have the certainty parents will intervene and use this as an opportunity for discussion… we have to make a different sort of decision.”

The fact that adults can check out Mein Kampf and other racist works from the library demonstrates the library isn't simply averse to controversy, Pateman said.

“Maybe there, we’d be privileging intellectual freedom because we’d say, most adults are able to make up their own minds,” he said. “They’ve got ways of putting this into context where children don’t.”

Alternative solutions to removing the books were considered, but ultimately came up short, Meady said.

“We even talked about having a shelf of controversial books that people could access and have discussions about, but it didn’t really fly, because it’s still providing that harmful depiction to children, and children are allowed to borrow freely.”

A complicated figure

While the conversation around racist depictions in Seuss’s books might feel new, it's been brewing for decades, Meady said.

“As early as the ‘70s, there were rumblings of some of the racist undertones there,” she noted.

In 1978, Seuss himself re-drew and re-described a Chinese character in Mulberry Street, first published in 1937.

“He basically said, 50 years ago that wouldn’t have raised an eyebrow – but now, it doesn’t seem appropriate,” Meady said. “Now even more time has passed, and you look at it and it’s still quite demeaning.”

Seuss remains a complicated figure, she said.

As a political cartoonist in the 1940s, he addressed anti-Semitism and anti-Black racism, while at the same time supporting the internment of Japanese Americans. His works contain allegories for inclusion along with crass racial stereotypes.

“He had a fairly advanced political view, but as a person of his times he also absorbed all of these tropes, and that was reflected,” said Meady. “We don’t want to see that carry on – we don’t want to see those racist depictions becoming part of what’s normal for children going forward.”

One of the ironies of the outcry around the books’ removal is that they were among Seuss’s least-read works, Meady said.

“Those books have been sitting on our shelves unloved and unpicked by people for a long time – [readers] have already sort of done their own deselection,” she said. “McElligot’s Pool hasn’t been performing for us for a long time, and probably would've just been weeded out [anyway].”

The impact of underrepresentation

Underrepresentation has very real impacts for racialized children, though it may escape the notice of many white readers, said Laura Prinselaar, a community hub librarian with TBPL.

“There’s a way of talking about the importance of diversity in literature that we use in the library world, and it’s about providing windows and mirrors for children – or for any reader,” she said.

“If the only mirror you have of yourself is this depiction that’s demeaning and hurtful and stereotyped… That can have a really negative impact, and it really means something. When you only have one example to choose from, the weight of that is different from [having] many role models, many examples you can see of yourself and your culture.”

Prinselaar stressed just how rarely people of colour are represented in children’s literature – something that’s only recently beginning to change, she said.

“I mean, there’s far more picture books with animal characters than that show families who are Black or have another racialized background – that’s a fact,” she said.

Pateman agreed, calling it a systemic problem in the publishing industry.

“There’s shockingly few Black authors of children’s picture books, for example,” he said. “It’s growing now… but for a long time, there were very few picture books that had even representation of other cultures, let alone positive representation.”

Building a diverse collection

That shows removing objectionable books is only a tiny part of the solution, staff agreed.

“We’ve been talking about things we’re removing,” Prinselaar said. “A big part of our work, probably a part we’re farther along with, is on the other side, building up the diversity and inclusiveness of our collection.”

The library has performed a diversity audit on portions of its collection including the children’s section. That resulted in the addition of several hundred new children’s books to diversify the collection, Meady said.

Library policies also favour “own voices” materials.

“Basically, it says if you’re going to have a book about a particular marginalized group, it should be written by an author who has lived experience," she explained.

Every book in the library's Indigenous Knowledge Centre is by an Indigenous author and/or illustrator, for example.

The "own voices" policy doesn’t deny books written from an outside perspective can be valuable, Meady said, but puts voices that had long been missing front and centre.

A higher standard

While it may be a smaller piece of the puzzle, the Seuss example shows there's likely more work to be done weeding out children’s books with problematic content, Pateman said.

“Maybe we need to [be more proactive] and do more removal of items from our collection that are sitting there at the moment very quietly, like the Dr. Seuss books were before this all exploded,” he said.

“We’ve got what I would call a healthy collection, but… there’s bound to be a few, or maybe more than a few, that won’t meet the new higher standard we’re going to be applying in the future.”

Meady agreed the Seuss books were likely not alone, but considered them an outlier.

“I can tell you with confidence we’re not going to find hundreds of books in our children’s collection that are akin to this situation," she said. “But when and if we do, because I’m sure there are some, we’ll look at them with the same scrutiny and intellectual rigour… every case is different.”

The library has vowed to seek feedback from racialized members of the community on its collections policies after removing the Seuss books.

The TBPL itself does not have any Black or Indigenous people around its management table, Pateman acknowledged.

Still, he said the library is working to be a genuinely anti-racist institution, and that the consultations would arm staff with better tools to build the best collection for the community.

“Just taking books off the shelves – I mean, it’s a form of action, but it’s pretty passive in some respects,” he said. “That’s why we want to take the second step of doing community consultation to look at our current collection management policy and make it even better than it is at the moment.”