The Wauzhushk Onigum Nation is welcoming millions in funding that will support a years-long process to identify and commemorate burial sites at a Kenora-area residential school.

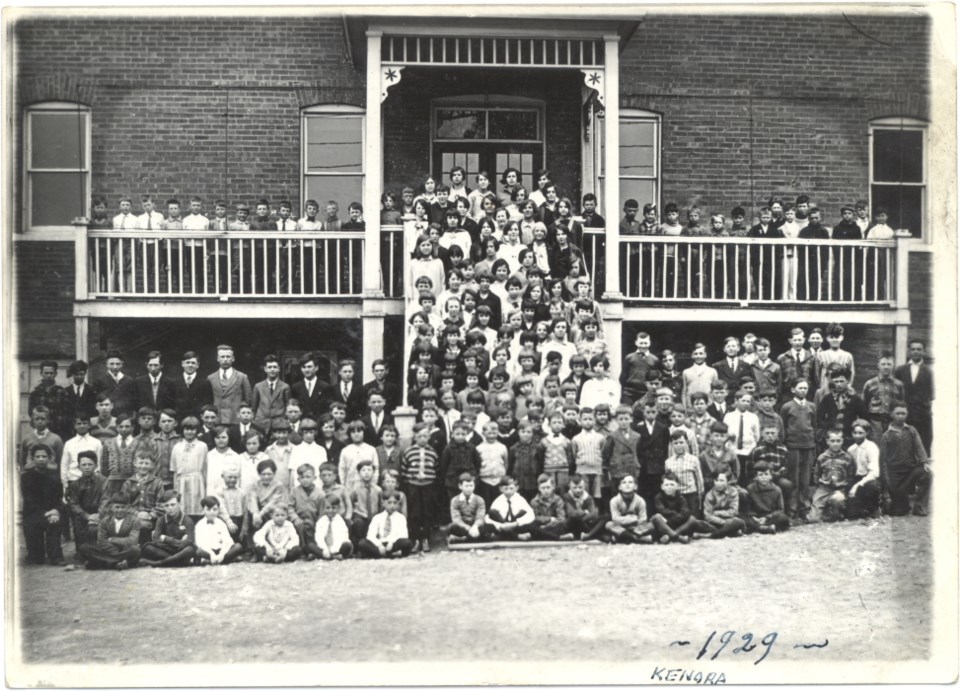

Roughly $2.9 million in funding was announced Thursday for the First Nation to investigate sites at St. Mary’s Indian Residential School, which was operated by the Roman Catholic Church from 1897 to 1972 just south of Kenora.

The Government of Ontario will kick in $400,000 of that amount, with the rest coming from the federal government.

Wauzhushk Onigum Chief Chris Skead said the commitment was belated but welcome.

“Our elders have been telling us for decades about the graves, the children who never came home,” he said. “It’s time to listen to their stories, and educate non-Indigenous Canadians about what happened to our people.”

The funding, which is spread over three years, will support engagement with survivors, gathering of oral history, the work of experts like archaeologists and ground-penetrating radar operators, mental health supports, commemoration, and possibly repatriation of the deceased to their home communities.

“The Wauzhushk Onigum Nation’s residential school Survivor project and the funding from Canada and Ontario represent the next step to support Indigenous-led, Survivor-centric and culturally sensitive efforts,” said Carolyn Bennett, Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations. “We will ensure that we will never forget those innocent children lost as a result of colonial policies.”

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation reported 36 confirmed student deaths at St. Mary’s, including two 12-year-old boys from Grassy Narrows First Nation who died after running away from the school in 1970.

The school was also one site of infamous nutritional experiments in the 1940s that caused anemia rates to spike among students, who were not made aware they were being used as research subjects.

It was one of five residential schools that operated on Treaty 3 territory.

A Truth and Reconciliation Commission report listed St. Mary’s as an example of a school where burial sites had been “abandoned, overgrown and overlooked.”

A cemetery associated with the school is documented in photographs from the early 20th century, but its exact location has not yet been identified, Skead confirmed.

“There are a lot of question still to be answered,” he said. “We don’t know yet [where the cemetery is located], and the St. Mary’s residential school grounds occupied a large area. It’s going to take us time to narrow down the search area.”

The process won’t be rushed, he said, both for those logistical reasons, and to ensure the process is driven by and respects survivors themselves.

“I had to really think about reintroducing the trauma, but we have the capacity as well as the support to help the survivors,” Skead said. “It’s definitely an emotional time and very difficult questions, but I know it’s definitely work that needs to be done in order to educate more mainstream Canada and the world, as well as for our own people here who aren’t even born yet, to have that story told.”

Everyone in the community is impacted by the history in one way or another, Skead said. In his own family, five generations attended St. Mary’s, he said, including his grandfather, mother, and some siblings.

There are 51 survivors of the school in Wauzhushk Onigum, he said. Discussions with those survivors have occurred over how to move forward.

Ground-penetrating radar will be used, Skead expects, and repatriation of the deceased will be considered, but that decision will be left to survivors in Wauzhushk Onigum and other communities whose children were sent to the school, he said.

Collecting comprehensive records from both the government and the Catholic Church will be paramount.

“We cannot do this work without transparency and records – we’ll need each and every record related to our children,” Skead said.

The community hasn’t heard from the Catholic Church, he said, but expects the institution will provide documents.

A 24-hour National Residential School Crisis Line is available to provide support to former residential school students at 1-866-925-4419. The Hope for Wellness Help Line is also available at 1-855-242-3310.