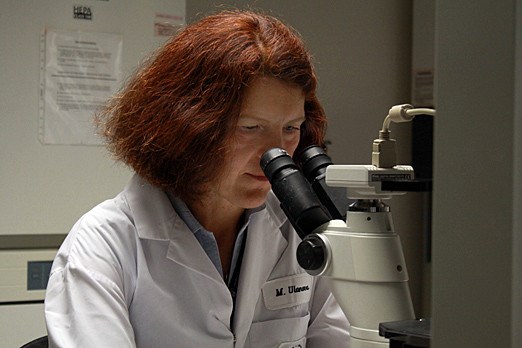

Immunologist Marina Ulanova has a medical mystery on her hands.

Haemophilus influenza type A, a bacterial infection, has caught the attention of the Northern Ontario School of Medicine researcher.

The particular infection appears to affect Aboriginals more prominently than other races. But the reason for this anomaly has yet to be uncovered.

Ulanova says there were 13 reported cases in Northwestern Ontario between 2004 and 2011 – the majority found in First Nation children living primarily in remote communities. Ulanova adds that this is an unusually high incident rate.

The Type A strain of the disease has been found as far as the Canada’s remote Far North, afflicting the local Inuit population.

“Several years ago we found an unexpectedly high rate of haemophilus influenza type A in the region that wasn’t described before,” Ulanova says. “That’s why I was interested in haemophilus influenza type A in Northern Ontario because this geographical area has a significant proportion of the indigenous population.”

She adds that those infected could develop blood infections, pneumonia and in some cases children develop meningitis. The disease can be deadly and in the Canadian Arctic the fatality rate for those contracting the disease was 16 per cent.

However, there have been no reported deaths from the disease in Northern Ontario.

Similar to the common flu, the infection can spread from person to person through sneezing and coughing.

A healthy person may carry the disease and unknowingly spread it to someone else.

Ulanova says researchers want to learn just how many healthy people are carrying the disease.

There are different variances of the bacterial infections that have proven to be manageable through immunization, including Type B of haemophilus influenza, which caused countless deaths before ongoing immunization programs brought it under control in 1991.

Ulanova says it was highly infectious specifically to the Aboriginal communities in Australia.

In order to combat Type A, Ulanova and her team collected a large sample from healthy adult First Nation volunteers in Thunder Bay.

She says they are now looking at their antibody levels and that the next step will be to look at Aboriginals who live in remote locations.

“There may be some differences in antibody between the rural communities and the metropolitan areas,” she says. “This is the stage that we are in now. We’re in the middle of the analysis and we’re recruiting more volunteers from northern communities.”

She adds that they have also taken samples from non-Aboriginals in order to do a comparison.

Having just begun the research stage, Ulanova said it’s going to be a while before any results will be published.

“We want to have this available for the public but the analysis takes time,” she said. “I think optimistically the first manuscript could be available around winter time. Expectations are in the spring we can take this data out to the public.”