BEARDMORE, Ont. - In the early 1930s, Eddy Dodd had a story to tell, and that story would change the world’s understanding of North American history.

It soon began circulating through bars and restaurants in downtown Port Arthur that the amateur prospector had unearthed a set of relics on his mining claim near Beardmore that proved Vikings had visited the Great Lakes.

This monumental story, one that came 30 years before the discovery of the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, eventually landed in the lap of one of the most powerful men in Canadian academia, lending it a high degree of credibility until it became accepted as fact.

But not everyone believed Dodd’s extravagant tale, and so began years of denials, cover-ups, speculation, and an amateur investigation by a local school teacher and a government geologist that would eventually reveal one of the greatest museum hoaxes of the 20thcentury.

Author and history professor, Douglas Hunter, examines the relic discovery and the investigation that followed in his new book, ‘Beardmore: The Viking Hoax that Rewrote History.’

“This is something that happened and these relics stayed in a major museum for 18 years and really changed history,” Hunter said. “It became: the Vikings came to the Great Lakes, they came down through Hudson Bay and a Viking died here, even though there was never a body, and it became history. It was taught in schools. That is how much influence this had.”

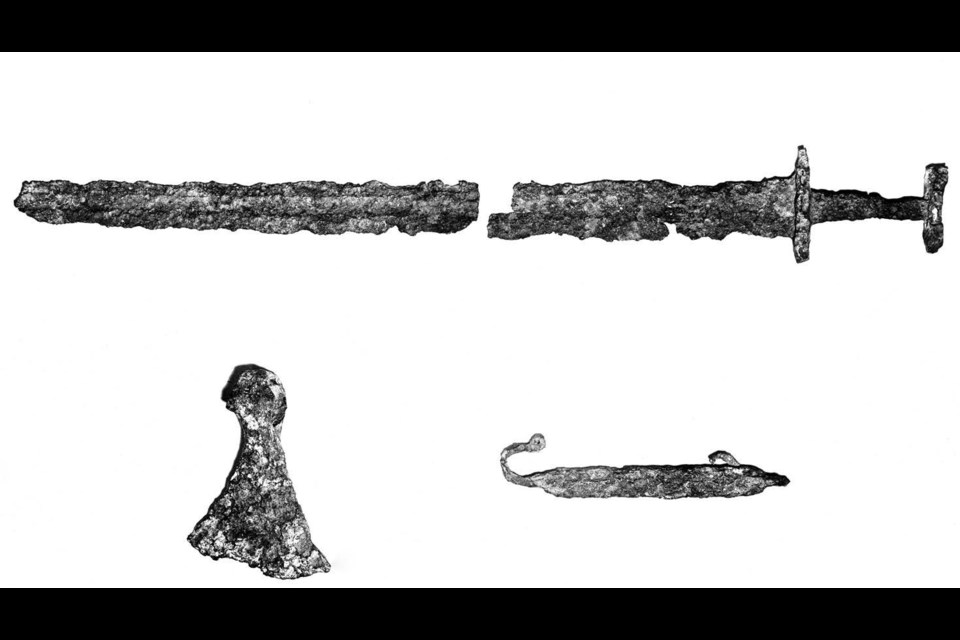

In May 1931, Dodd claimed he found what appeared to be a sword, an axe head, and a piece of metal that may have come from a shield when filling a trench with dynamite on his mining claim southwest of Beardmore.

Word about the discovery eventually reached Charles Currelly, curator of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. In 1936, Dodd sold the relics to Currelly for $500, or approximately $7,000 today and the relics were prominently displayed in one of Canada’s largest museums.

“Currelly bought them and he bought the story,” Hunter said. “After 1938 when some serious counterclaims started emerging in the Thunder Bay and Winnipeg area that no, Eddy didn’t find them in the ground in his mining claim, he found them in the basement of a house he was renting.”

The relics themselves are authentic and according to Hunter, there is a likely chain of possession that landed them in Dodd’s hands. The relics most likely belonged to John Bloch, who came to Port Arthur from Norway and used them as collateral for a loan from a local man named James Hansen. The loan was never repaid and Bloch left Port Arthur and later died in Vancouver. So the relics remained in Hansen’s basement, where, Dodd happened to be a renter.

But what didn’t add up and what Currelly failed to do, was look more closely at Dodd’s story about where he claimed to have found the relics.

Investigation uncovers the truth

High school teacher, Teddy Elliott, and government geologist, T.L. Tanton, were among the most vehement sceptics of Dodd’s claim, and began their own investigation into the authenticity of the story. But Currelly refused to yield, which Hunter said demonstrates how those in power can sometimes dictate what is true, even if it is false.

“It’s an interesting study in how power is exercised,” Hunter said. “It’s not just about a hoax, it’s about how authority can use power. Currelly kind of gambled all his cultural capital of himself and the museum on this one acquisition. If Currelly said this stuff was real, it was hard to disagree with, especially if you were a newspaper person.”

It would take nearly 20 years before it was revealed that the Beardmore relics were a hoax. Hunter said Currelly wanted to believe the relics were real and this was a hoax that “didn’t fit the standard mold.”

“When we usually think of hoaxes in museums or art galleries, what we think of is some sophisticated forger who pulls one over on the smart people,” Hunter said. “What we have here is a different kind of fake. We have authentic artefacts but they are in the wrong place.”

The discovery of the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland in 1960 did prove that the Vikings travelled to North America. But for a time, the Beardmore relics completely changed the world’s understanding of North American history.

And while it is not completely outside the realm of possibility that Vikings travelled through the Hudson Strait and into Hudson Bay or James Bay and then down into Northern Ontario, many scholars agree that it is unlikely.

“People have a hard time imagining what Norse people would be doing in the Great Lakes,” Hunter said. “It doesn’t fit with their pattern of travel. They were farmers, homesteaders; they were looking for resources on a coastal basis.”

‘Beardmore: The Viking Hoax that Rewrote History,’ reads like a detective novel, Hunter said, because it is “a detective story about a detective story.”

“There are very clear characters and there are just a lot of very strange twists,” Hunter added.

And the story that started it all, told by the man at the heart of this hoax, it might have been just that – a story to get people talking, not about the relics, but about a mining claim near Beardmore.

“Eddy Dodd didn’t set out to start this sophisticated crime and take in the ROM,” Hunter said. “He wanted to get people interested in his claim. It was basically, as long as he had the relics, he could get people talking about his claim.”

People are still talking today about that story first told nearly 90 years ago about a discovery, a hoax, and an investigation that rewrote history.

‘Beardmore: The Viking Hoax that Rewrote History’ is published by McGill-Queen’s University Press and was released on Sept. 15.

Douglas Hunter will be in Thunder Bay on Tuesday, Oct. 23 as part of the Thunder Bay Historical Society lecture series at the Thunder Bay Museum.