THUNDER BAY -- By his own estimates, Clint Malarchuk says he should have died three times.

The former NHL goaltender was nearly killed on the ice on March 22, 1989 while playing for the Buffalo Sabres when the skate of St. Louis forward Steve Tuttle slashed his neck, sending a cascade of blood flooding to the ice, his life hanging in the balance.

A quarter-inch deeper and he’d be dead.

He survived, and miraculously 11 days later, defying the advice of his doctors to retire or take the rest of the season off, he was between the pipes again.

It was too soon, only he didn’t know it at the time.

Malarchuk fed off the adrenaline of the fans, who cheered his every move upon his return.

“I was like a rock star in Buffalo,” he said on Monday during a speech in Thunder Bay on behalf of the local chapter of the Canadian Mental Health Association.

What fans didn’t know was that Malarchuk had silently suffered anxiety attacks his entire life, symptoms only going away while he was on the ice.

The injury brought many of those childhood fears and panic attacks roaring back.

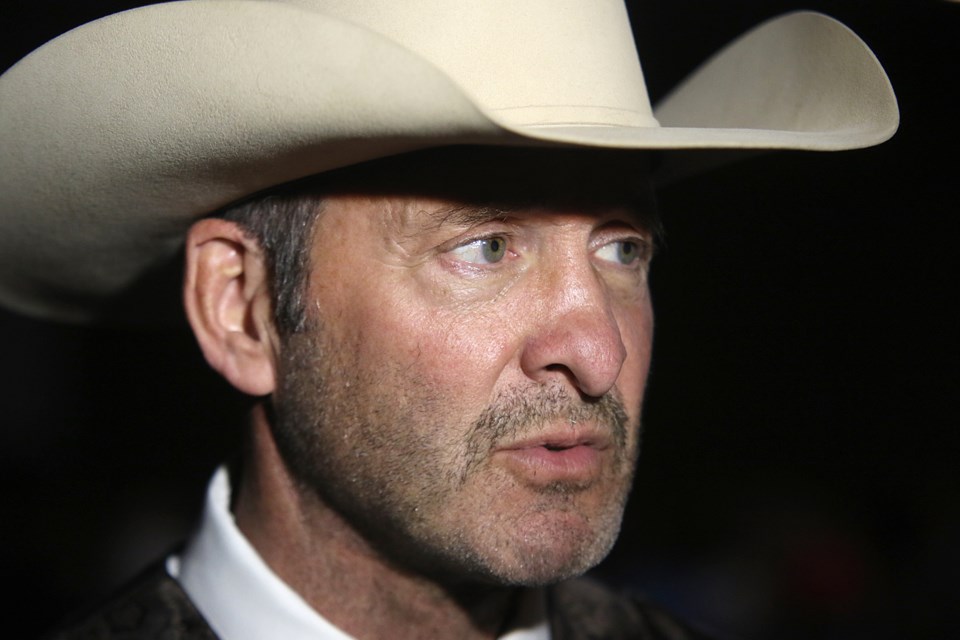

“The things I dealt with as a kid growing up were pretty minor compared to the things I dealt with after the injury,” said the cowboy-hat-wearing Malarchuk, a comical, tell-it-like-it-is 55-year-old who has tried his hand at coaching and horse dentistry since his playing days ended for good in 1997.

“After the injury I sunk into a very deep depression. I was very obsessive compulsive. It was hard for me to leave the house. I was having wicked nightmares and I guess now they call it post traumatic stress syndrome.”

He began to drink and take pills to sleep. His heart stopped and he was rushed to the hospital, treated and for the first time, his mental instability was diagnosed and a treatment program was begun.

Things were going well.

That is until 2008, when another NHLer, Richard Zednik, had his carotid artery slashed by a teammates skate.

The bad memories came flooding back, as journalists turned to Malarchuk for comment.

Soon he was drinking up to 28 beers a day and later that year, unable to take the pressure, he turned a gun on to his head and pulled the trigger, shattering his chin and palette. The bullet remains lodged in his head to this day, the doctors unable to operate for fear of killing him.

“What I really wanted to do was to kill the pain,” he said. “I didn’t want to die, but I didn’t want to live the way I was, in pain. And it’s real pain.

“People don’t understand. They understand cancer. That person, they’re laying there and it’s eating at them and they’re in so much pain. That person wants to live, but they don’t want to live in that pain. Mental illness is no different.”

Malarchuk, who would spend six months in a clinic, hit rock bottom when he awoke and told his wife, “See what you made me do?”

Six years later, after finding a treatment regimen that restored the chemical imbalance in his brain, Malarchuk bared his soul in The Crazy Game, in which he talks candidly about his life, his alcoholic, mentally ill father and offers advice to those suffering from mental illness.

“I survived for those who still suffer,” he told the crowd, admitted he had to be pressured into writing the book.

“I felt it would help people as I asked ‘Why was I spared?’

The demons have mostly disappeared, but every once in awhile they’ll return in small doses.

But that’s OK, said Malarchuk, who believes the two most important days in a person’s life are the day they are born and the day the figure out why they were born.

“I haven’t conquered them all. I still struggle. But I’m doing good.”