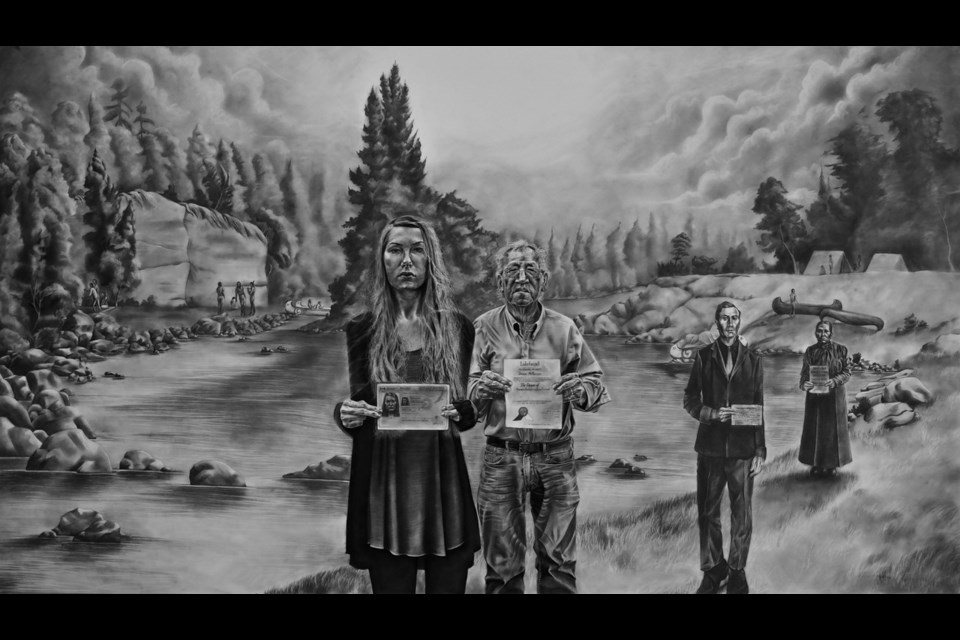

Mary McPherson’s art leaves the eyes mesmerized. A true, almost unbelievable marvel, her drawings bring questions, connection and awe in a form not normally recognized when a person gazes, slowly, at an artform in front of them.

She is an Ojibwa artist and member of Couchiching First Nation. After receiving her bachelor of fine arts, with a minor in Indigenous learning, from Lakehead University, McPherson is now pursuing English common law at the University of Ottawa. There she intends to strengthen her understanding of how Canadian law impacts Indigenous peoples.

McPherson began focusing on her art in high school after seeing what was missing from her education within the Thunder Bay school system. A lot of her artwork in high school expressed her family history in regard to residential schools and how it was left out of the curriculum.

“I was learning one thing in school, going home and my family was critiquing it according to my family history,” she says.

Through her art, and now her legal education, McPherson is exploring what it means to have a governmental identity under the Indian Act and to further understand her family history under Treaty 3.

Legislated identity

Introduced in 1876, nine years after Canada’s inauguration, the Indian Act laid out rules for the assimilation of the Indigenous people. It was in the Act that Indigenous children were forced to attend residential schools, a topic McPherson touches in her art.

“There’s this outside perception of who we are that’s being perpetuated through the education system and we’re constantly subjected to that.”

McPherson also discusses The White Paper from 1969, formally known as the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy.

The goal of this legislation was to abolish the Indian Act but in a way that eradicated the treaties, thusly obliterating the reserves. This would have affectively assimilated the Indigenous community.

McPherson feels this kind of legislation should be a continuous discussion and wants to further explore the ways in which it’s occurring. “I really want to look more into aboriginal law and further understand how the law applies to status Indians…I don’t think it’s talked about enough.”

Rising through history

A lot of McPherson’s work has been questioning who Indigenous people are. She explores how the government has implemented assimilation measures in the form of legislation and what it means to grasp onto these legal issues and continuously questions what the community is being told.

“It’s the responsibility of the community to know and own their identity; the reality of their core values.”

Through the traditional practices of her community and family, and how it’s translated and morphed into modern day, McPherson discusses her familial history.

Her aunt attended a residential school and during her time in this institution, she was taught to crochet. These crochet works would be taken and sold to make money to run the residential school, an institutional form of child labor, she says

Her aunt took this artform and adapted it to her own experience and continued to crochet her whole life. She discovered pride and value in work she was doing for herself that was rooted in her experience of repression.

“We’re living in a world where oppression continues, and we’re constantly being fed perceptions of who we are; we’re constantly being faced with divisive practices and lateral violence.”

An educational curve

McPherson learned that she had to change the way she was thinking fundamentally in order to get close to grasping a deeper understanding about the information she was being taught.

“I felt torn in two."

She was coming into law school from an experience through the reflections of her life, her family’s life, and her community’s life. She came to the understanding that she had to assimilate to the information she was being taught; she had to understand the violence in learning.

“You have to deform yourself to the information to fundamentally get a grasp on it, to learn it.”

McPherson began to transform. She grasped onto this curve through her education and is seeing it from an enhanced perspective; understanding topics and concerns from a legislative perspective she’s previously addressed in her art.

Making headway

McPherson knows and believes the system of support in Thunder Bay is massive; in the Indigenous and artistic community. She was shocked by the lack of Indigenous students in Ottawa and would like to see more Indigenous students pursuing legal education.

Through education and consideration, she sees the work being done to move forward. “There’s a lot of stereotypes that tell us what an Indian artist [is] and what Indian art looks like.” McPherson says.

She’s taking these stereotypes, these interpretations of what’s assumed of her community, and presenting the truth behind them.

And the work is continuous. She believes two things need to happen. One of those being openness and consideration from the settler population by learning the history.

“This will facilitate an environment where settlers can better understand the differences and we can start to embrace and respect each other.”

For Indigenous people, she wants the community to find pride and responsibility in who they are.

“I think finding pride in ourselves [we] will set an example for youth to follow.”

McPherson expresses this and presents it to the world through her art. And now, through her legal education, she’s assisting the community of Thunder Bay to grasp onto a culture rooted in the land. A culture flowing through history and into the future. And with the ability to listen, understanding will follow.